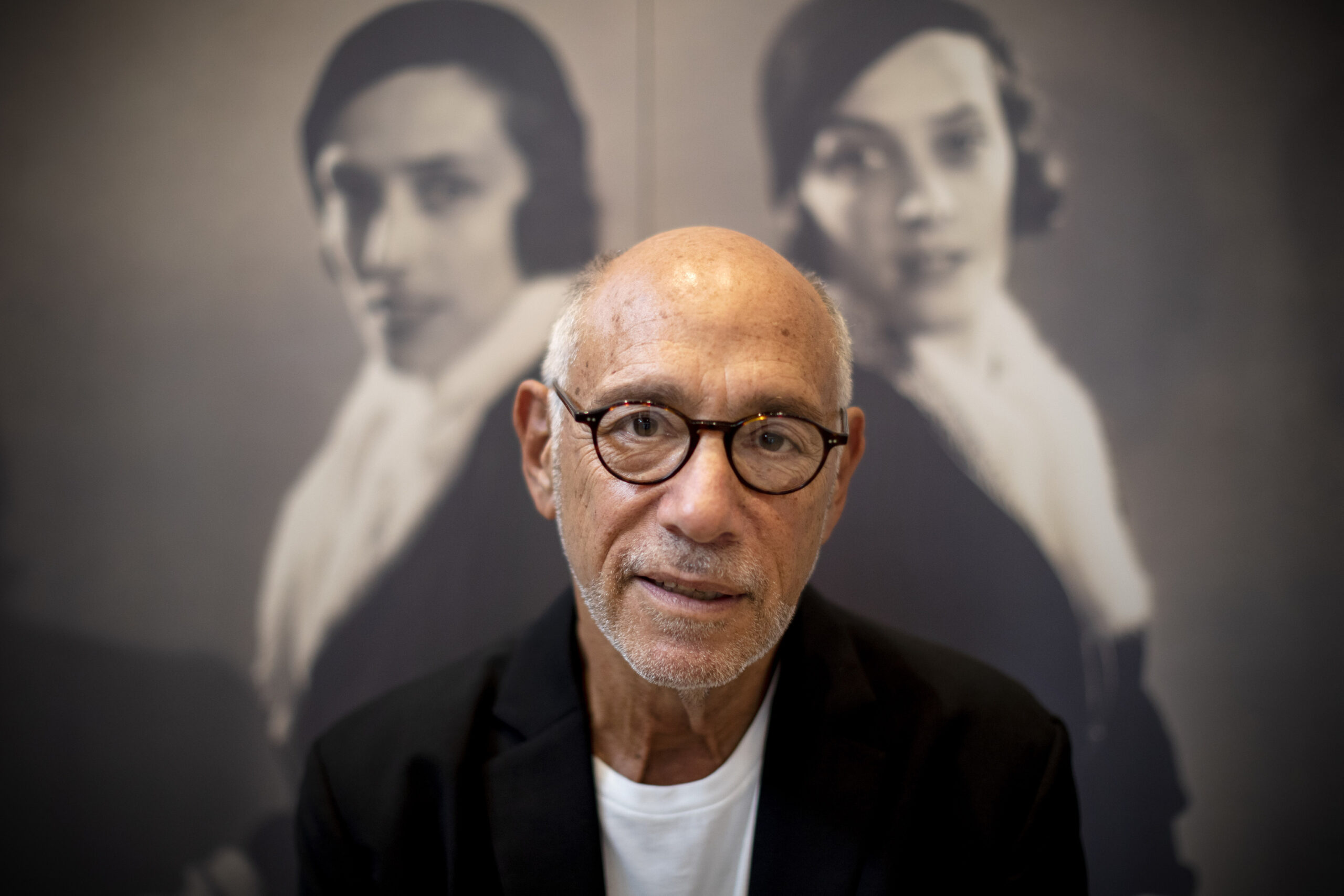

Howard Greenberg (New York, 1948) appears in the lobby of the hotel where he is staying in Madrid with a very Larry David energy: round glasses, a groomed bald head, a casual air, a cheerful step and a coffee in his hand. Both are Jewish from Brooklyn and barely a year apart, so the reasonable resemblance between the comedian and the photo-dealer patriarch has a curious geographical backing. Greenberg is in Spain to talk about his professional career at a meeting organized by the Fundación Canal, whose exhibition hall in Mateo Inurria, 2 hosts until July 24 Uncovered, an exhibition curated by Anne Morin with 111 rarely seen images of the nearly 30,000 stored in the immense archive of his gallery in Manhattan.

His story began half a century ago in Woodstock, the small town in upstate New York where Bob Dylan still lived at the time and was universally known for the legendary music festival held in 1969. Greenberg moved there in 1972 after dropping out of his Psychology studies. with the intention of being a photographer. He went to work at the local newspaper, and that opened the doors to a deep-rooted artistic community of which he immediately became a part. His passion for images crossed with his love of collecting, and he began to buy old photos at flea markets and auctions. In 1977 he founded the Woodstock Photography Center and in 1981 he opened his first gallery: «When I opened it I stopped taking photos because I realized that I couldn’t do both things well. And it was much easier to be a gallery owner than a good photographer, so I gave up photography », he jokes.

Although the medium was beginning to arouse commercial interest, at that time it was still possible to acquire masterpieces by authors such as Edward Steichen or Alfred Stieglitz for relatively modest amounts compared to the prices of painting or sculpture. But in 1984 there was a turning point when the Getty Museum in Los Angeles decided to create a photography collection and allocated 30 million dollars from that time. «Little by little, that money was reaching all of us who dedicated ourselves to this. They bought $150,000 worth of work from me, who had a modest gallery in a town. The Getty Foundation money changed the market and changed my life.” That movement attracted investors in the process; the idea was consolidated that photography, that artefact that according to Susan Sontag «simultaneously deals with the prestige of art and the magic of reality», had value.

Thanks to this, Greenberg was able to move his gallery to New York. It was in 1986, a time of ferment in the art world that photography benefited. And he became the king of his own, a sort of guardian of the 20th century canon, with an extraordinary nose for rescuing forgotten authors, like Saul Leiter, and finding unpublished work by unknown photographers in basements and attics. His previous experience behind the camera and in the darkroom has given him an edge in appreciating the technical aspects of the material he works with.

The golden age of the classic photo market lasted until the end of the 1990s, when prices of up to six figures were paid for rare copies of the great photographers of the 20th century. But soon after the balloon began to deflate. Due to excess supply. It was when the hundreds of copies that authors such as André Kertész or Cartier-Bresson, taking advantage of the general interest in photography, had put into circulation at relatively affordable prices during the 1980s, returned to the market. «The auctions became saturated with too many identical photos and that pushed prices down,” recalls Greenberg. “Only the market for the best vintage, for special historical copies, which are increasingly scarce and attract collectors with a higher purchasing power, held up and has continued to rise and rise in price until today.”

The devaluation of historical photography coincided with the vertiginous appreciation of contemporary photography. “Everything changed when photographers started showing their work in art galleries,” he explains. And dealers discovered that very few copies of large-format images could sell for very high prices. “For the same reason that a large painting doesn’t cost the same as a small one, galleries sell large photos for more money. It’s natural », he adds, sympathetic but skeptical of a phenomenon that in his opinion has long since crossed the threshold of what is reasonable.

Integrated into the feverish dynamics of the contemporary art market, current photography has captured the interest of collectors to the detriment of historical photography. The exclusive and monumental copies of a Wolfgang Tillmans have cornered the black and white miniatures of Josef Sudek like the ones that can be seen at the Canal Foundation. “Today’s culture is not as interested in the past as it was in the old days. In the 70s, people bought photos with historical value, looking for a connection with the past. That has changed. Young people today, especially those who have made money quickly and can afford to collect, don’t feel that connection. It is a feature of contemporary culture that is reflected in photography and in art in general. The contemporary covers everything».

Greenberg now runs his business between New York, Berlin – where he has moved with his current partner – and Ibiza. In 2018 he sold his personal collection to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. “I am no longer young, and collecting anything takes a lot of time and effort. I formed it when it was possible to access incredible material. And that is no longer possible.”

Conforms to The Trust Project criteria