The French president, Emmanuel Macron, remodeled the government on Monday without major changes to face a second term that seems difficult for his reformist and liberal agenda, after losing the absolute majority in Parliament.

Macron “reached out four times to the opposition to put all the options on the table. They said no,” said an adviser to the executive, for whom the “presidential majority” is thus “the only one that exists.”

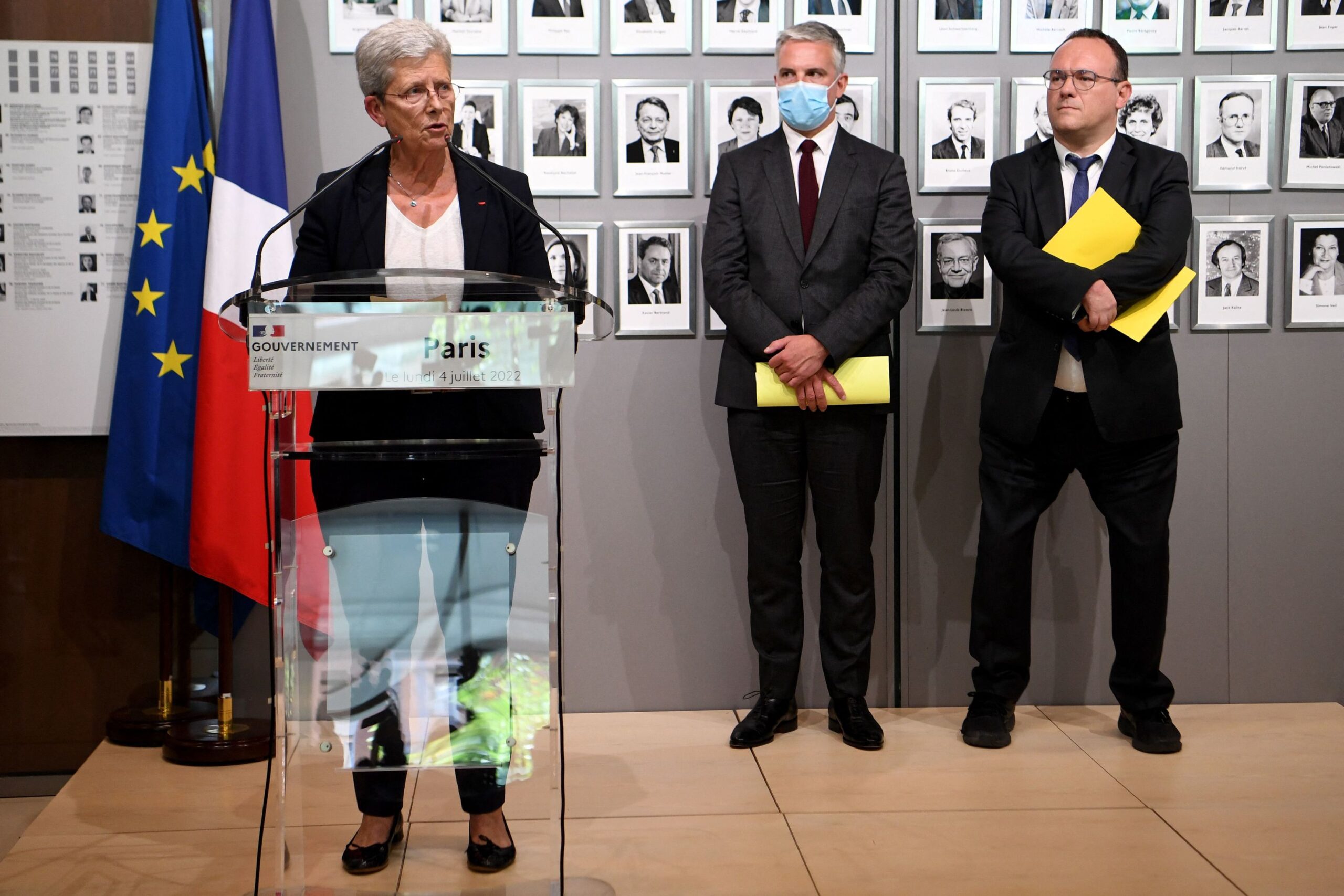

With 250 deputies and 39 of the absolute majority, Macron reinforced the weight of his allies and completed the government led since May by Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne, but without in-depth changes after failing in his attempt to gather support.

The most notable announcement is not the entry of new ministers, but the departure of one of the three members of the government accused of rape, Damien Abad, who was responsible for Solidarities, Autonomy and Disabled People.

His appointment in May was presented as a right-wing signing, but revelations days later of alleged sexual assaults weighed on the executive. The French justice opened last week an investigation for attempted rape.

“It was preferable that, in the face of vile slander (…), I could defend myself without hindering the government’s action,” said Abad, who thanked Macron for his “trust” before passing the baton to the director general of the French Red Cross, Jean-Christophe Combe.

Although they are also the subject of rape complaints, two other members of the Borne government – which will continue to be equal with 21 men and 21 women, although the former occupy the majority of high positions – remain in office.

The prosecution asked to file a complaint against the Minister of the Interior, Gérald Darmanin, who now also assumes Ultramar, at the beginning of 2022. Secretary of State Chrysoula Zacharopoulou is facing lawsuits from three women for rape, during Zacharopoulou’s tenure as a gynecologist.

The most prominent entry into the new Borne government is that of Laurence Boone, current Chief Economist of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), as the new Secretary of State for European Affairs.

His predecessor Clément Beaune, Macron’s “Mr. Europe” since he came to power in 2017, will now serve as Delegate Minister for Transport, after winning ‘in extremis’ a deputy seat in the June legislative elections.

Under an unwritten rule, ministers who ran for a seat and were unsuccessful had to leave the executive. Three did not make it: Amélie de Montchalin (Ecological Transition), a friend of Macron, Brigitte Bourguignon (Health) and Justine Benin (Sea).

Greenpeace lamented the government’s “lack of vision” in appointing Christophe Béchu, “a policymaker with no experience” on climate issues, as the sixth Minister for Ecological Transition in five years.

The emergency doctor François Braun will assume Health in the midst of the seventh wave of covid-19 infections and the deputy Hervé Berville, a Rwandan orphan evacuated at the beginning of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, will be Secretary of State for the Sea.

This remodeling marks in practice the beginning of the second term of the centrist president, two days before the general policy speech of his prime minister, and closes a period of uncertainty since his re-election on April 24.

The new government did not convince the extreme right or the radical left, the main opposition groups in the Assembly (lower house), but neither did the formation that seeks to attract the ruling party to weave majorities: The Republicans (right).

The far-right Marine Le Pen accused Macron of “again ignoring the verdict of the polls” and the leftist Mathilde Panot considered that the remodeling symbolizes “a power in decline”, after failing to attract members of other parties.

Although the opposition hopes that Borne will submit to a confidence vote after his speech, the arrival of many deputies in the government suggests that this usual practice will not take place. The decision is not yet made.

Borne, on the other hand, has already begun negotiations with the opposition on his first bill, a package of measures that seeks to protect purchasing power and whose adoption is expected by the end of July or the beginning of August.

The rise in prices – especially fuel and food – due to the war in Ukraine is the main concern of the French and a warning signal for Macron, whose first term was already marked by strong social protests.

Conforms to The Trust Project criteria