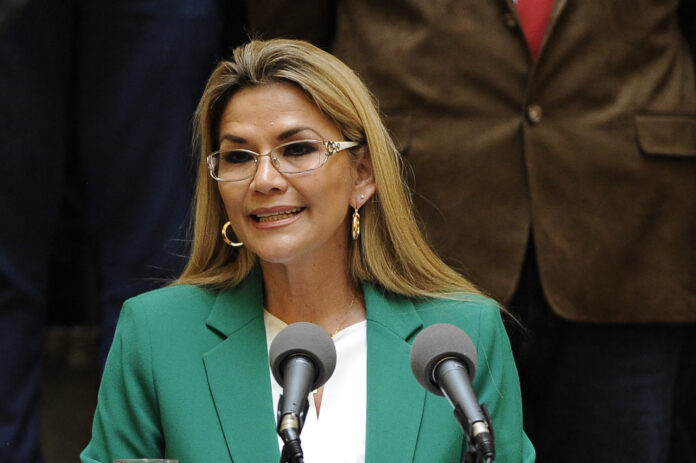

The First Sentencing Court of La Paz did “justice” against former president Jeanine Áñez, who has been sentenced to 10 years in prison after a trial fraught with irregularities. For the Bolivian judges, the former senator is guilty of the crimes of “breach of duties” and resolutions contrary to the Constitution” during the succession of the resigned Evo Morales, a process that included the participation of the European Union, the United Nations and the Bolivian Church.

The electoral fraud carried out by the ruling party, and discovered by the Organization of American States (OAS), triggered an avalanche of citizen protests in 2019, which was followed by the police stand-up in Cochabamba, who refused to repress the population, the distancing of different public positions and the “recommendation” of military commanders to the leader of the indigenous revolution. Morales later fled to Argentina and Mexico, which opened the succession that allowed Áñez, an unknown opposition deputy, to access the transitional presidency.

Former Commander Williams Kaliman, then head of the Armed Forces, and former Commander Yuri Calderón, head of the Police, were also sentenced, although they have fled the country.

Initially accused of terrorism, sedition and conspiracy, Áñez has not even been able to appear in court, because there was a “flight risk” according to the judges. “They have denied me the right to be present even at my own trial, if that is what this drill can be called. They have denied me everything and treated me worse than anyone, but I was, am and will be the constitutional president who assumed her duty after the flight of the coward”, defended the former president, who has denounced repeated ill-treatment.

The “coward” is former president Evo Morales, who yesterday showed his enthusiasm after hearing the sentence: “Despite the lies and actions to say that she was ill or about to die, the justice system ruled that Áñez and her accomplices assaulted power with a coup d’état. Ten years in prison is a benign sentence in relation to the damage they caused to democracy”.

The conviction against Áñez immediately provoked a carousel of denunciations and criticism “in the face of one of the most infamous political crimes in Bolivian history, by using the servile justice system to convict a former constitutional president without any evidence or crimes. The setback of democracy and the rule of law is shameful,” complained Carlos Mesa, precisely the former candidate against whom the 2019 electoral fraud was carried out.

Áñez’s mandate, of a single year, was marked by the pandemic, several corruption scandals and the internal struggles of the opposition, which in the end facilitated the return to power of the Movement for Socialism (MAS), with Luis Arce at the helm. The indigenous revolution is today the great continental ally of the three Latin American dictatorships.

“She is being judged for a crime not committed. Historically, there is a history of constitutional presidential successions with errors of form but which avoided bloody confrontations. The senator took office by resigning in dominoes from the other authorities in a violent context. Bolivia is today among the last 10 places in the world with a lack of judicial independence,” historian Lupe Cajías revealed to EL MUNDO, who observes behind the sentence a tug-of-war between radical sectors of the MAS.

“Añez’s conviction is repudiable not only because of her identity, a mestizo woman without power, but also because of the politicization of justice in force in Latin America. With the Brazilian Dilma Rousseff there was clamor; with Áñez, silence. You don’t have to sympathize to condemn. More human rights and less militancy and hegemonic creeds,” protested historian Armando Chaguaceda, one of the continent’s leading specialists on revolutions.

The plot of the coup d’état in Bolivia has also become one of the masterpieces of the alliance of populists, leftists and revolutionaries, who call themselves the Great Homeland, whose aim is to recover the continental hegemony they already enjoyed during the presidencies of Hugo Chavez and Lula da Silva.

The last to make it clear was the Argentine president, Alberto Fernández, who during the Summit of the Americas accused the OAS of being a “gendarme” and of being behind the “coup d’état” in the Andean country. The sentence against Áñez is necessary to maintain the story of both those who lead the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), which aims to replace the OAS, and the Puebla Group, one of the main whitewashers of the revolutions in Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua.

Conforms to The Trust Project criteria