Olesya Novitskaya did not hesitate for a moment when the occupation authorities began issuing Russian passports in Melitopol, a city in southeastern Ukraine conquered by Moscow’s forces. “We were waiting for him,” she says.

AFP spoke with this 31-year-old professional make-up artist as part of a press trip organized by the Russian Ministry of Defense to show the welcome given to the occupants by the population.

The journalists were not allowed to move freely in the city or talk to the inhabitants without being accompanied by a Russian military escort.

Accompanied by her two children, Novitskaya was in a line of about twenty people waiting to ask for her Russian documents.

“I think we will all live in Russia, so I need a Russian passport. To be able to live here officially and normally,” he explains to AFP with a child in his arms.

The occupation authorities of the Zaporizhia region, where Melitopol is located, want to organize a referendum at the end of the year to formalize the annexation to Russia.

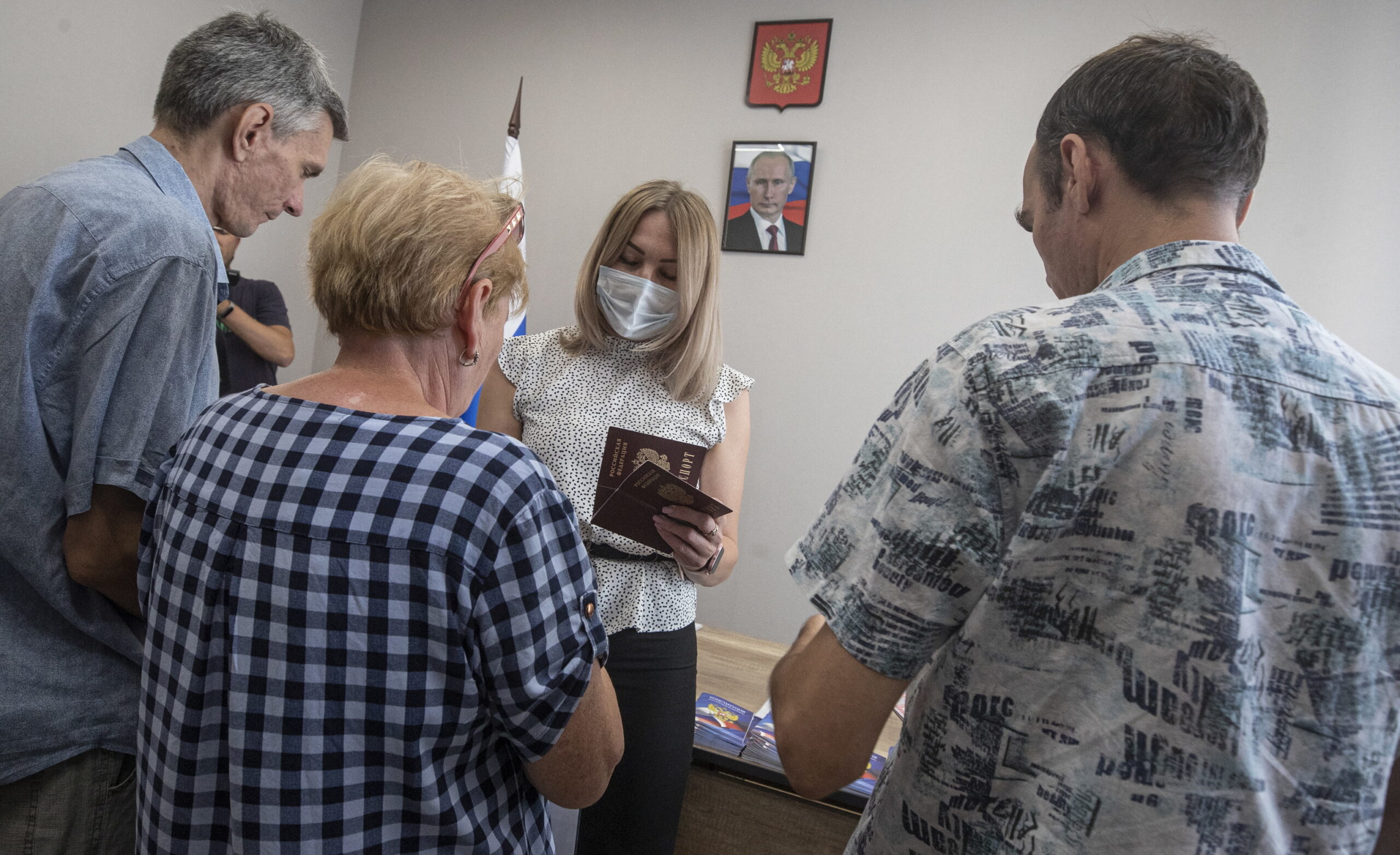

After a few weeks of waiting, Novitskaya is due to receive her new documents at a ceremony in which the Russian anthem will be played in front of a portrait of Vladimir Putin.

This distribution of passports, which also takes place in other occupied Ukrainian areas, is part of Moscow’s strategy to establish itself in the region irreversibly.

Other measures include the payment of salaries and pensions in rubles, the Russian currency, the inauguration of train and bus lines connecting with the Crimean peninsula annexed in 2014, and the opening of Russian-language schools.

Melitopol was taken by the Russians shortly after the start of the offensive on February 24. There was almost no fighting in the city, which prevented it from being destroyed.

At the time, the Ukrainian army was defending kyiv, the capital, and Mariupol, a port city that had been besieged and shelled for weeks.

This July, the Russian military presence is discreet, but there are still roadblocks at some exits from the city. But Novitskaya doesn’t mind.

“To be honest, we expected that in 2014,” the year the Crimean peninsula was annexed and the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine with pro-Russian separatists began.

However, she recognizes that not all the population thinks like her. “Today, the whole world is divided,” she says. “Some are for Russia, others for Ukraine,” she notes.

She considers herself Russian, like many inhabitants of this region where Russian is the dominant language. “For my son who was in the second year of primary school, it was difficult to study in Ukrainian,” she says.

Also waiting in line is Damir Kadyrov, a 65-year-old retiree who believes it is “necessary” to obtain a Russian passport after the arrival of the Russians in Melitopol.

“Since they have decided to finish off the fascists, things will be calmer, like in Soviet times,” he said, echoing propaganda from Moscow, which claims to be fighting “fascists” and “Nazis” in Ukraine.

But seeing the figures, this enthusiasm is far from being shared by all the inhabitants of Melitopol, which before the Russian offensive had about 150,000 inhabitants.

The head of the regional occupation administration, Yevgeny Balitsky, acknowledges that only 20 to 30 passports are distributed daily in that town and “about a hundred” throughout the region.

The pace “is not up to par yet,” he lamented, while pointing out that the controls of the Russian security services are delaying the process.

Added to this is a general climate of mistrust. Those who support Ukraine fear Russian repression. And those who prefer Russia fear being considered “traitors” or “collaborators” by supporters of kyiv.

In fact, part of the people who were in line to ask for passports preferred to leave before the arrival of television cameras and a Russian military procession in front of the administrative building.

“We don’t talk” about Russian passports “among ourselves,” admits Galina Vladimirovna, a 58-year-old resident. “It’s still taboo, everyone is afraid,” she says.

Conforms to The Trust Project criteria