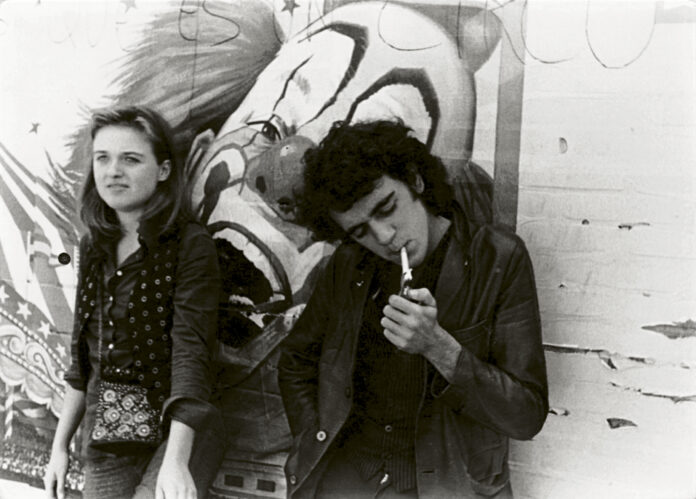

Much has been written about La Movida, about how the movement channeled the yearning for freedom and social change in Spain in the 1980s. These were the years of the decriminalization of homosexuality, in December 1978, and also of the legalization of the sale of contraceptives, in April of that same year, with all that this meant for the sexual life of millions of Spanish women. Along with Alaska, Ana Curra and Paloma Chamorro, Ouka Leele was the female face of La Movida.

Despite the highly publicized airs of revolution and liberation, things must not have been entirely easy for the women who shone the most in Madrid’s new wave. “I think photography was a way out, because the couple I was with forbade me to paint. And I let them forbid me. It was the law of terror, as you paint you will find out,” confessed Ouka Leele herself three years ago years in an interview with Efe, where she reflected on the fact of being a woman and an artist. “We have to give a lot to achieve the same level, to get paid the same, to be treated the same. We give a lot, we work a lot, we are like heroines. I believe that art has no gender, that we are all male and female inside “.

Niece of the poet Jaime Gil de Biedma, whom she met in bars at night, her career as an artist took off in Barcelona, where the underground woke up somewhat earlier than in the capital. There she had her first exhibition, at the Spectrum gallery, and it was Star magazine, an icon of the Catalan counterculture, that published her first cover. Cancer struck her for the first time when she was very young, at the age of 22, and she brought her back to Madrid. “My generation was crushed by the war, my father spoke of it all the time as something heroic. I think that’s why we all accepted each other, regardless of origin, sex, ideology or surnames,” he confessed in another interview with this diary two years ago.

“At that time I was like an angel,” he recalled about the 1980s on the occasion of an exhibition at the Fotocolectania gallery where his mythical series Peluquería was exhibited for the last time along with the work of fellow photographers such as Miguel Trillo, Alberto García- Alix and Pablo Pérez-Mínguez. At that time, he defined domestic mysticism, his particular philosophy of life and creation, with a candor somewhere between costumbrista and Zen: “Love what you do, even if it’s sweeping the house. Anything you do, like cleaning a glass and seeing how it shines, it’s the best thing you can do at that moment. It’s happened to me: going through a difficult time, concentrating on making some croquettes and having it heal.”

Over the years, Ouka Leele hardened the discourse of her art without ever losing sight of the feminine. A cruel banquet. Pour quoi?’ was the title of the installation she created in 2014 to denounce the war in the Republic of Congo, where gold, diamonds and coltan left a trail of six million dead and a chilling average of 160 women raped every week. In 2006, she brought together 300 people, including women, men and children, for Revive Cibeles, an intervention in the Madrid square to raise awareness in society against ill-treatment. It was not the first time that traffic in the square had stopped: it had already been done in 1987 for Rappelle toi, Bárbara!, the fantastic blockbuster where she represented the myth of Hippomenes and Atalanta, the beautiful huntress who hated the idea of getting married and challenged everyone her suitors to a race against death through the forest.

«What great loneliness that of the woman whose fatal destiny leads her to be admired, to dare to do things that the society of the time in which she has lived does not understand or does not dare to see. She is desired by all, but loved by none”, she wrote in her latest book, Axis Mundi.

Conforms to The Trust Project criteria